- Home

- Walsh, Barbara

August Gale

August Gale Read online

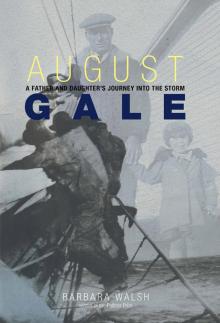

A U G U S T

A FATHER AND DAUGHTER’S JOURNEY INTO THE STORM

G A L E

BARBARA WALSH

Guilford, Connecticut

Copyright © 2012 by Barbara Walsh

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, P.O. Box 480, Guilford CT 06437.

Map on page 256 by M.A. Dubé © 2012 by Morris Book Publishing, LLC, based on a map from the government of Newfoundland.

Maps on pages 257 and 258 by M.A. Dubé © 2012 by Morris Book Publishing, LLC, based on research and sketches done by Con Fitzpatrick.

Project editor: Meredith Dias

Text design: Sheryl P. Kober

Layout: Joanna Beyer

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN 978-0-7627-6146-3

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my parents, Ronald and Patricia Walsh, who have always had faith in me

CONTENTS

Preface

Walsh Family Tree

CHAPTER 1: A Sudden Wind—Brooklyn, August 1935

CHAPTER 2: Lured by the Gale—Maine, February 2002

CHAPTER 3: The King of Marystown—Newfoundland, 1935

CHAPTER 4: The Family Storm Unravels—New Hampshire, 2002

CHAPTER 5: “’Tis Nothing but Worry and Waiting”—Marystown, August 1935

CHAPTER 6: Victory Ships and a San Francisco Tempest—My parents’ kitchen, April 2003

CHAPTER 7: Gathering a Crew—Marystown, August 1935

CHAPTER 8: The Sisters Gather—Newburyport, Mass., May 2003

CHAPTER 9: Father McGettigan’s Torment—Marystown, late August 1935

CHAPTER 10: Pictures of the Past—Maine, June 2003

CHAPTER 11: A Premonition and a Dark Cloud—Marystown, August 1935

CHAPTER 12: Heading into the Storm—Newfoundland, June 2003

CHAPTER 13: Mustering Courage on Board Annie Anita and Mary Bernice—August 21, 1935

CHAPTER 14: “Welcome Home”—Marystown, June 2003

CHAPTER 15: The Tempest Roars North—North Atlantic, 1935

CHAPTER 16: Chasing Ancestors—Marystown, June 2003

CHAPTER 17: “There’s a Divil Coming!”—Newfoundland Fishing Grounds, August 1935

CHAPTER 18: Mountainous Waves and Mighty Men—Marystown, 2003

CHAPTER 19: Prayers and Apparitions—Marystown, August 1935

CHAPTER 20: “My Poor Daddy Was Lost”—Marystown, 2003

CHAPTER 21: Shipwrecked Schooners and Bodies Swallowed by the Sea—Newfoundland, 1935

CHAPTER 22: “The Whole Town Just Stumbled into Shock”—Marystown, 2003

CHAPTER 23: McGettigan’s Grim Task—Marystown, August 1935

CHAPTER 24: A Final Voyage—Marystown, 2003

CHAPTER 25: “’Tis the Queerest Wake”—Marystown, 1935

CHAPTER 26: Ambrose Continues to Haunt—Marystown, 2003

CHAPTER 27: Digging Up the Grave—Marystown, 1935

CHAPTER 28: Graveyards and Redemption—Marystown, June 2003

CHAPTER 29: The Storm Still Lingers—Marystown, 1935

CHAPTER 30: August Thunder and Ambrose’s Daughters—New Hampshire, August 2003

CHAPTER 31: “Left in a Dreamland”—Newfoundland, 1935–2005

CHAPTER 32: One Last Journey—Brooklyn and Staten Island, October 2006

Acknowledgments

Glossary of Newfoundland and Nautical Terms

August Gale Storm Track

Where Paddy and James Sailed

Houses of Fishermen Who Died in the Storm

The Walsh Tragedy Song

About the Author

PREFACE

August Gale started out as a story about a storm and my seafaring ancestors who were caught in a killer hurricane, a “devil” that descended upon Newfoundland’s waters in the summer of 1935.

But it turned out to be much more. The story grew to include my grandfather, a man who created his own tempests and abandoned my father as a young boy. It would have been much easier to just recreate the gale and my Great Uncle Captain Paddy Walsh, but stories have a way of changing course, becoming living, breathing entities.

My grandfather Ambrose Walsh was Captain Paddy’s younger brother. Though I tried to exclude Ambrose from the book and focus only on the fishermen who battled the sea, my grandfather’s past, his connection to my father and my family, haunted me. I soon learned I had to tell his story, too.

A journalist for thirty years, I had written about killers, rapists, corrupt politicians, and the victims of crimes, accidents, and misfortune. Their stories were often difficult to tell—but they were strangers. I had never written about my family. The thought of writing about my father’s pain, his childhood hurt, overwhelmed me. I trust you, he repeatedly told me.

Over the past nine years, August Gale took my dad and me on several journeys. We traveled to Newfoundland to gather memories from our ancestors and the children whose fathers fought for their lives in a roiling sea. We traveled to Staten Island and Brooklyn, where churches, playgrounds, and rough-and-tumble neighborhoods stirred the memories of my father’s turbulent past.

More than 150 people shared their recollections about a hurricane that forever changed a small Newfoundland village in 1935. And scores of my family members—aunts, uncles, cousins, and my father—helped me to understand the grandfather I never knew.

All the events in this book are true, and the characters are real. In some cases, the dialogue was repeated to me by someone who witnessed the event or the conversation. In other instances, I had to recreate dialogue to retell a scene. In preparation, I reviewed hundreds of pages of newspapers, government documents, and hurricane data to confirm facts, details, and personal accounts.

Nine years have passed since my father first told me the story of the August Gale; for nine years I have lived with this story in my heart and in my head. It is time to let it go, let it be told.

As my seafaring friends would say, “Hoist the main, heave the anchor, and let ’er sail!”

CHAPTER 1

A SUDDEN WIND—BROOKLYN, AUGUST 1935

Ambrose Walsh sits alone on a bench. The pungent odor of fresh fish and the pleasant scent of saltwater waft through the air, reminding the young man of his Newfoundland home. In the distance, the Staten Island ferry chugs across the bay, churning up waves that slap the Brooklyn pier. Ambrose eyes the diminishing ship, his mind drifting like the plumes of steam billowing from the ferry’s engine. He is uncharacteristically distracted at this moment, perhaps by the euphoria of his first son’s birth, a dark-haired boy born just two weeks ago; or perhaps he is consumed with worry like any other family man, hoping that he doesn’t end up in the relief line with his hand out and his pride gone.

A stranger passing Ambrose on this afternoon would admire his ink-black hair, dark eyes, thick chest, and strong arms. His shoulders and back are taut, straight. Though he is only twenty-seven, he can handle himself in a fight or on a job, and in this year of 1935, he needs all of this strength to believe the future holds more than the past. A strange and sudden gust, a warm August breeze, pulls Ambrose from his thoughts. Sheets of newspaper drift in the air and tumble along the pier until they reach the bench where the young man sits. Glancing down at the trash, Ambrose considers letting the wind take it further along the gritty Brooklyn wharf, but the summer breeze rattles the paper as

if it were calling, demanding his attention.

Finished with lunch, Ambrose considers returning to work, but something draws him to the newspaper that has remained at his feet despite the wind that swirls around him. He bends to pick up the paper, scanning the front-page stories. A bold headline captures his eye: AUGUST GALE KILLS MORE THAN 40 NEWFOUNDLAND FISHERMEN.

Ambrose is not a man who panics easily, but now fear constricts his throat, making it difficult for him to breathe. He has been gone from his home, the small Newfoundland fishing village of Marystown, nine years. There had been nothing for him in the rural outpost; he never had the stomach for or the desire to battle the sea like his four older brothers. When the demand for exporting cod and salt fish prices began to tumble in the 1920s, Ambrose decided it was time to explore other opportunities.

He had barely turned eighteen when he filled his duffle and hugged his mother, Cecilia, good-bye. “You’re too young to be leaving, boy,” she’d told him. She didn’t like the idea of losing her youngest child, her mischievous “Tom Divil” to a country so far from her village doorstep. Yet she harbored little doubt that Ambrose could charm his way, flash his smile, and endear himself to women and men alike. And sure now, he wasn’t the first of her boys to head for America. Her son Leo had done the same years earlier, like so many Newfoundlanders looking for opportunity and a better life.

“Don’t forget us now,” she had scolded. “I’ll be praying for you, son.”

Ambrose hadn’t thought much of Marystown since he arrived at New York City’s Penn Station, the enormous train depot that made him dizzy and delighted all at once. Never before had he seen so many people in one place, hurrying in dozens of directions, heads bent with purpose. Ambrose was eager to find his own purpose, a good job, a fair wage. His older brother Leo, who lives in Staten Island, had promised to get him hired at his place of employment, a company called Procter & Gamble. Ambrose had never heard of this American company or its famous Ivory soap, but his brother Leo assured him that a man could do well working for them.

From the moment he arrived, Ambrose has chosen to cut off communications with his Newfoundland family. A man prone to keeping secrets, he now guards the details of his new life, understanding that his silence will make his mother think the worst: that her youngest son is dead or in some horrible trouble. Still, neither he nor his brother Leo sends letters to Marystown about Ambrose. No word about his home in Staten Island or his marriage to Patricia O’Connell, a shy, blonde-haired girl with kind blue eyes.

On this August afternoon, Ambrose has an aching desire to return to Marystown, the rows of houses on the bay, the families bound by blood and sea. The guilt of abandoning his family weighs on him now. He is afraid to read more of the newspaper story, more of the killer gale. A betting man, fond of gambling and playing the horses, Ambrose knows the odds of losing family in this storm are great. Most of his brothers, uncles, and cousins still earn their living from the sea. Surely his oldest brother Paddy was out in his schooner, hoping to make his final catches for the long winter months ahead.

Ambrose allows himself a grin at the thought of Paddy shouting orders to his crew as they prepared to sail from Marystown: “Heave up the anchor, boys!” There would have been singing on the deck, the crew’s voices blending together as they heaved the anchor and hoisted the sails. Ambrose knows that nothing thrilled Paddy more than sailing schooners. He lived for fishing from one season to the other. Paddy knew where to find the cod and how to handle the sea when it grew rough.

“You’re missing the adventure, boy,” Paddy had often chided him. “A man should be at sea. Come out and crew for me. Come and fill yur dory with fish. We’ll fight the sea together.”

Ambrose had tried to embrace Paddy’s love for fishing. Briefly, he considered it, imagined himself hunting cod and sailing schooners, all the while his heart telling him there was no measuring up to Paddy.

Twenty-one years older than Ambrose, Paddy is more like a father than a brother. Ambrose’s own father, Tom Walsh, is old enough to be his grandfather, and any fatherly instincts have long been spent on his first eleven children. It was Paddy whom Ambrose had sought as a youngster, longing to be in his presence, wanting what Paddy had: confidence and the courage to face whatever challenges came his way.

Now on this Brooklyn wharf, Ambrose would give anything to hear Paddy tell another story, the two of them sitting beside the kitchen cooker, laughing late into the night.

Ambrose hasn’t enough money in his pockets for the fare home to Newfoundland; there is no hope of seeing Paddy or anyone else in his family. He has little doubt that his mother, along with every woman and child in Marystown, is on her knees, whispering the Rosary for the missing men. He cannot say his own prayer, begging God to keep his family safe from the storm. Ambrose has never believed in the Lord no matter how much his mother tried to persuade him otherwise, and he is not about to change his mind now for even the most desperate of causes.

Though the August sun warms his face, Ambrose is bone cold, as if he himself had fallen into icy waters. He is afraid to learn more about this killer storm, yet he cannot ignore the paper pushed to his feet by a sudden wind. His dark eyes scan the report of sunken schooners and scores of missing men. He finds the words that cause him to cry out.

Like his brothers and the generations of Irish ancestors born before him, Ambrose Walsh is not in the habit of revealing his fears or emotions. Yet on this day, as the ferry carries him across New York Harbor to his Staten Island home, he curses and moans. The wild look in his eyes frightens the other passengers. When he arrives at his doorstep, his voice hysterical with grief, his wife, Patricia, hushes their baby, as Ambrose, himself, weeps like a child.

CHAPTER 2

LURED BY THE GALE—MAINE, FEBRUARY 2002

My father is the first to tell me about Ambrose and the August Gale. He shares the story with me one winter evening, realizing that he has never recounted it to anyone since his mother had told it to him forty-odd years earlier. He finds it strange that the story has lain dormant in his mind for so long.

Yet this does not surprise me. My father, Ronald Eugene Walsh, was the baby Ambrose’s wife hushed that August afternoon in 1935, the dark-haired son whom Ambrose would abandon eleven years later.

For most of my life, Ambrose was a mystery, a taboo topic. When I was a child, I asked my Nana where Grandpa was. She quickly told me, “He’s dead.” I do not remember asking more about him. In my seven-year-old mind, I accepted that Grandpa didn’t exist. I could not see or touch him; I did not know his name, and no one ever spoke it—not my father, not Nana, nor my uncle. There was no evidence of Ambrose, no photographs of him in our home or my grandmother’s.

I was eighteen before I learned my grandfather was alive. The revelation occurred when my older sister Diane and I drove my dad from our New Hampshire home to the airport in Boston, Massachusetts. During the ride, Ambrose’s name came up. I do not remember if I pressed my father for details about my grandfather’s death, but he suddenly explained, “Ambrose isn’t dead. He’s living in California with another family.”

“He’s alive?” I repeated, stunned.

There was little time to ask more questions before we pulled to the airport curb for my father’s flight. Grabbing his bags, he hugged us good-bye, and I watched him disappear beyond the airport door.

I turned to my sister, who strangely did not seem as surprised at the news about our grandfather. “Can you believe that Ambrose is alive?”

“I knew he was in California,” she replied nonchalantly. “Nana used to tell me about him.”

“What? How come no one told me?” I asked, hurt.

Despite my shock over Ambrose and his mysterious California family, my grandfather quickly slipped back into a place best left untouched, forgotten. Asking questions about Ambrose was like touching a hot stove. My five sisters and I knew it would cause pain. During our teenage and college years, random phone calls from our mysterious grandfat

her stirred my father’s anger, leaving him silent, brooding. Occasional books, letters from California were quickly discarded. If anyone dared to utter Ambrose’s name, my father fell silent or left the room, unwilling to acknowledge the man he could not forgive. Years before I was born, the guests at my parents’ wedding were told that Ambrose was dead. It was easier than answering questions about a man who abandoned his family—twice, on distant American coasts.

Now on this winter evening, my father talks about Ambrose and the August Gale. I fall silent, unconsciously holding my breath, afraid that if I speak, it will stop my father from continuing, from giving me a gift: a story about my grandfather.

We sit, side by side, on my living room couch as a distant foghorn echoes in the woods out back. My father is three years shy of turning seventy. His broad-chested, five-foot-eleven-inch frame is still intimidating, a characteristic that helped him in the amateur boxing ring and in the brawls he fought as a young Navy sailor, touring the world. Though his hair is gray and thinning, decades of yard work and a lifetime of sports have kept my father trim, muscled. His brown eyes hold a newfound softness—a benevolence—and they remind me of my Nana’s kind blue eyes. My father has softened in other ways too. During the past few years, he has begun telling me and each of my five sisters after every phone conversation: “I love you.” My voice always catches as I return the salutation, understanding that his parting words illuminate a shift, an emotional sea change. Though I have never doubted his love, my dad has long guarded and buried his feelings. Now, at the age of forty-four, I am beginning to understand why.

On this February night, his voice is low, mesmerizing, as he shares what he knows about the 1935 Newfoundland hurricane. While my father speaks, his large hands cut the air to emphasize his thoughts. Later I will learn he has his father’s hands—Newfoundland hands—strong and suited for hauling cod. He describes how the foreboding newspaper landed at Ambrose’s feet carrying news of the deadly storm; how Ambrose feared his hero, his older brother Paddy, was dead.

August Gale

August Gale